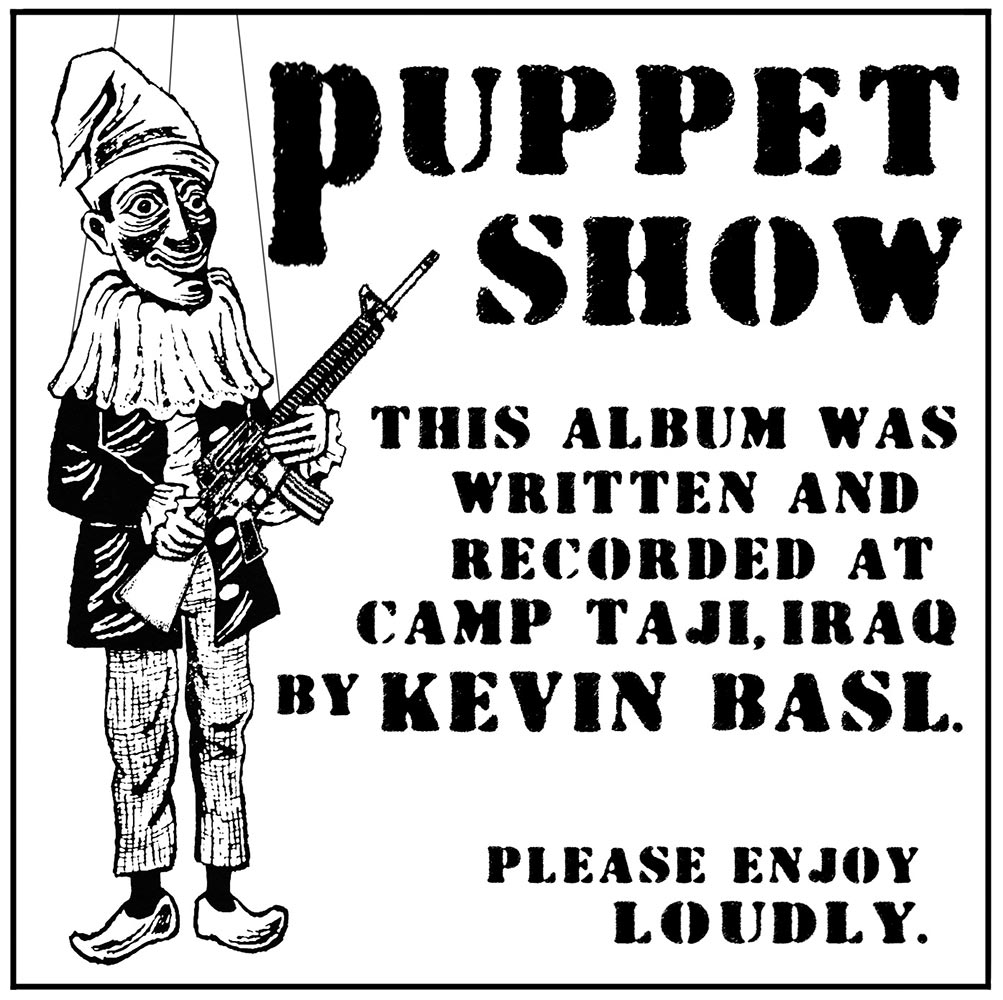

The Photo on My Parent’s Entertainment Center

A rust-toned semblance of me

costumed in Hollywood battle rattle

stands before the stars and stripes

backdrop we all know

from elementary school.

I borrowed a SAW-249 machine gun

because they are sinister

and beefed up my chest.

My M-16 rifle, shoulder-slung

like a broad sword,

compliments a bayonet

un-tactically hung

from a loop on my flak vest.

A grenade pouch filled

with either gauze or toilet paper

is the bulge alongside my gas mask;

a belt of ammunition hangs

a python around my neck.

On the floor, detonator wires

from a plastic claymore mine

tangle in a thorny mess

alongside my helmet, an improvised

footstool for my clunky desert boot.

My vacant gaze aims

at some forgotten profundity

hovering in the ozone,

as I mimic a George Washington pose.

Or maybe I'm the statue David

dressed up for trick or treating.

How I should have smiled like a clown

before that Iraqi merchant's camera—

or sent that shot to the burn barrel.

But off it went to quiet Mom's nagging

for a look at me in desert uniform,

her wanting to see

the pride of war.

To my Grandma,

aunts and cousins

old teachers and the preacher

mom passed it out like a country mailman.

And I haven't the heart nor guts to tell.

Why I Answered the Call for Veterans to Go to Standing Rock

At Standing Rock, for the first time, I felt like I was finally serving the people.

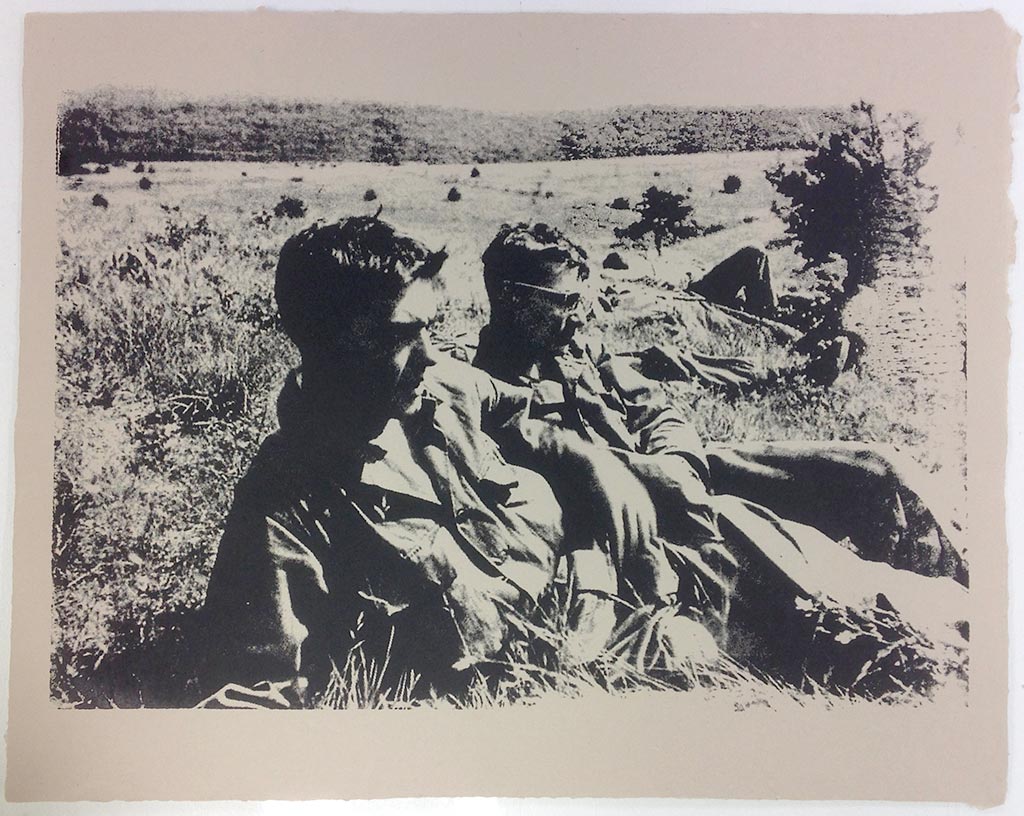

I lay among friends, huddled and cold in our sleeping bags. We listened to the lashing wind and the drums and prayer chants coming from the sacred fire, and we reflected on why we, four Iraq War veterans, were here.

Police floodlights shone from the drill site of the Dakota Access Pipeline, scheduled to cross under the Missouri River, the water source for millions of people.

Members of the Standing Rock Sioux, concerned not only about polluted water but also the desecration of sacred sites, began resisting the pipeline in 2014. In mid-2016, finally, these water protectors gained major support.

Over 200 tribal nations pledged solidarity. Thousands of non-natives traveled to North Dakota to stand on the front lines. Then, as images of police violence against protectors got increasingly disturbing, some 4,000 veterans — including me — joined the resistance in early December.

Why had so many veterans taken up the cause of the Native Americans and environmentalists at Standing Rock?

My own reasons are rooted in western Pennsylvania’s coal country, where I grew up. There, I rode my bicycle on trails crossing abandoned strip mines. Bulldozers had left precarious shale formations and streams ran orange with iron runoff.

When a sanitation corporation threatened to open a landfill at a reclaimed mine near homes in our community, residents finally resisted. At age 15, I joined the fight to stop the dump, gaining a deeper appreciation for the wildlife — and water — of my region. Good jobs are scarce in my hometown, so military service is something nearly every boy — and now girl — considers. My grandfathers both served, along with several uncles.

Back home, the military is sacrosanct. But I wasn’t especially proud of my five years in the Army, two of which were spent in Iraq.

My job as a radar operator, like so many military specializations, got privatized, so I found myself tasked out for other duties. I guarded poor Iraqis while they filled thousands of sandbags for the contractor Kellogg, Brown, and Root, only to see those sandbags rot in the sun as they sat unused.

I also loaded caskets onto cargo planes — an image often hidden from the American public. And I escorted high-ranking officers on unnecessary trouble-provoking missions (how else could one earn the Combat Infantry Badge?).

Like many post-9/11 veterans, I left the military seeking redemption. Perhaps that’s why, after I saw those images of police violence against water protectors, I went to Standing Rock.

There, instead of helping military contractors make money, I felt like I was finally serving the people.

While we were there, on December 4, the Army Corps of Engineers finally denied the pipeline company its permit to drill under the river. Police pulled back, and the water protectors celebrated.

The indigenous community had worked months for this ruling. They sacrificed the most. But I like to think the result was also influenced by the prospect of police tear-gassing and firing rubber bullets at unarmed veterans.

A ceremony followed where Wesley Clark Jr., key organizer of the Veterans Stand for Standing Rock campaign, offered an apology to Native Americans on behalf of the military, citing decades of broken treaties and violence. Five hundred of us went to our knees.

I hope to participate in a forgiveness ceremony one day in Iraq, in the spirit of Standing Rock.

Reunion Dance

It all ends here:

The doors part

and I walk into the dull

fluorescence

of a parking garage

dripping with rain water,

acres of concrete,

late night humidity.

I cannot cry.

Like a tired hitchhiker,

I bear my duffel’s burden

and consider my presentation:

posture as a soldier,

love like a son.

You can read a person

in his eyes alone

my drill sergeant said.

The stress, the hungry void,

the breaking point—it’s present,

the weight now carried

in all the wrong places.

My father, one year later,

a carpenter’s muscles

fallen to an old man’s paunch,

my mom’s eyes

crow’s feet and quiet desperation.

They watch me approach,

two seniors on a blind date

posing for the prom.

The Noise Remains

Sunlight reflecting off a stainless steel coffee maker

forms a howitzer round

on the refreshments table at the university job fair,

where I try to convince myself

a nine to five is the purpose of my life.

The zip-tie holding up the muffler on my neighbor’s Suburban

reminds me of blaze orange detainees,

their wrists bound, heads sandbagged

and slouched in shameful prayer.

A Lysol-clean classroom tastes like the Dental Corps tent

where I “manned up” for a root canal

because they don’t give Novocain in the combat zone,

not to soldiers, not to kids.

Can you hear the chalice drums,

louder than cannon fire,

the beat of five hundred thousand dead hearts?

I confess.

I enlisted for an honorable crime

to erase a felony from my record.

I pointed my rifle like a rich man’s cane

to direct Iraqi teens mixing concrete,

slaves constructing a perimeter

to block mortars shot from the dusty fields

of their fathers.

Teeth fell from the mouths of those curious boys

who got in the way, who reached out

to touch Kevlar skin, coarse hands–

and the same thing now happens to me

when I open my mouth to speak,

standing naked and bone thin

before an audience of ghosts

in the worst dream of all

this is who I am,

who we‘ve become.

Jessica Lynch

is not my name.

David Petraeus spits in my face

when he writes “How We Won in Iraq.”

Did George W. Bush

really happen?

My story is my own,

and it ends in loss.

Like a gunshot in a basement,

the remains of a thousand explosions shout

(buzz through my skull)

Iraq

drowning out

the moral of these words.

And what remains is a burning whisper:

to enjoy myself

is to forget our routines

are held together

by fragile agreements

tested and broken in war.

Wake Up Call

Six days before Sergeant Justin Crossnew’s

fifth deployment

our chaplain

came to say

no morning

accountability

formation

and remain

in the barracks

until our

silver-starred

squad leader

had been cut down

from the third story

fire escape

where he had double–

wrapped paracord

around his neck

and let himself hang

for the whole world to see.